People tuned into news from Palestine are often surprised to hear that one of the occupied West Bank’s main industries is tourism. Tourism has provided livelihoods for people in many cities in historic Palestine for centuries; there was even a tour guide’s guild in early Ottoman Jerusalem. Palestine has long been a destination for religious pilgrims, and particularly Christian tourists have continued making pilgrimages, constituting the vast majority of the tourists entering Israel and the West Bank every year. Despite the prominence of pilgrimage tours, recent decades have seen a rise in other forms of tourism to the West Bank. While alternative forms attract smaller numbers, they are no less important as gauges of political realities, in how Palestine is both marketed and perceived.

The New York Times’ Palestine coverage in March provided some glimpses into the eclectic variety of visitors travelling to the West Bank. The 17 March NYT magazine included a long article featuring the village of Nabi Saleh. While it was the villagers and not their guests who were the focus, the article touched on the wide array of foreign and Israeli activists, tourists, and journalists who regularly spend time in the village, particularly to take part in demonstrations. Nabi Saleh’s weekly demonstrations against land confiscation and settler encroachment have become notorious for the fierce army crackdowns they inspire. These crackdowns have resulted in countless injured Palestinians and internationals, and more than one death. The Israeli army detained the journalist who wrote the story, Ben Ehrenreich, when covering a demonstration. In a major Israeli public relations fail, Ehrenreich received a call on his cell phone while he was waiting in detention. The army spokesperson promptly informed him to report that no journalists had been detained. By being in Nabi Saleh on a Friday, Ehrenreich witnessed an enduring part of Israeli occupation, military violence used against unarmed people defending their village.

Just over a week later, NYT Jerusalem bureau chief Jodi Rudoren profiled a very different view of Palestine and a very different type of visit: that of Israeli tourists. These particular tourists were not the Israeli activists who join the demonstrations in Nabi Saleh, nor were they visitors in the way that Ehrenreich was. They remained mostly in Area A and primarily on their bus, in a fashion not unlike the enclave tours popular among mass tours of pilgrims. These Israeli tourists are the occupiers, and not just in a vague associational way because of what passport they incidentally hold. Some had been to Ramallah before, one as recently as 2006, “as a soldier,” he said. “Inside a tank.” This visitor reflected: “I used to drive into these places at five o’clock in the morning, when it was pitch black. It’s nice to see it alive.” In this journey, the former soldier had a ‘civilian’ permit to enter, since Area A is legally off-limits for Israeli entry without a government issued permit. There is of course, the exception of when Israelis come rolling in on a tank. Both types of entries happen frequently enough to make the rule a total farce. [1]

As an example, in the same week as the Israeli tour group visited Ramallah, Palestinian news agency Ma’an reported that the Israeli government granted permits to a group of Israeli settlers to make a trip to Solomon’s Pools, a significant tourist site outside Bethlehem, but still in Area A. PA officials were publicly furious about this trip, and pledged that they would take action to prevent it. The trip went on without a hitch and Israeli military escorts accompanied the settlers. Similar trips, such as those to Joseph’s tomb in Nablus, happen frequently. The settlers of Gush Etzion, one of the largest settlements on the West Bank, are also well-known for hosting Israeli and international tourists at their shooting range.

Here we have a rough sketch of several types of tourist itineraries in the West Bank, aside from the pilgrimage tours. There is ‘political’ or ‘solidarity’ tourism, through which places like Nabi Saleh, otherwise unheard of for most tourists, become prime attractions. This type of tourism also includes less demonstration focused fact-finding missions. There is settler tourism, tours to settlements in the West Bank or tourists from West Bank settlements to Area A locations. And there is a third type of tourism, demonstrated here by the Israeli group, which seems at first to defy the available categories, but as I will argue, is far less of an anomaly than it may appear.

The trip was organized by the Israel Palestine Center for Research and Information (IPCRI). IPCRI is a normalization project par excellence, founded together by Israeli and Palestinian entrepreneurs to promote Israeli-Palestinian cooperation and achieve a two state solution. Its co-founder is Gershon Baskin, a self-declared politician and “expert.” [2] The other notable figures on the IPCRI board boast connections to the World Bank, Al Quds Investment Bank, several Israeli colleges, and last but not least, the PA. While it does not seem that any current PA officials are involved, the board includes the former PA Minister of Energy, and a former top-level PA political advisor.

The itinerary looks fairly benign and even familiar to many of us who have been involved in solidarity tourism. It could even appear to be Palestinian nationalist, and arguably more so than the suggested itineraries promoted by the PA Ministry of Tourism on their website and in their materials (for Ramallah, the official PA tourism website suggests mostly trips to ruins, restaurants, and shopping). This group visited Arafat’s grave and the new museum dedicated to Mahmoud Darwish (one participant was disappointed that Hebrew translations of Darwish’s poetry were not displayed). They went on to look at a neighborhood adjacent to the apartheid wall. They continued to a ride around the central city square, the Manara (where they did not get off the bus). They ate in a Ramallah hummus joint, hurried upstairs to a private seating area.

These itinerary items are usually called “alternative tourism” in the Palestinian context, as they are certainly an alternative to the dominant form of Christian pilgrimage mass tourism. The pilgrimage tours usually arrive in the West Bank from their bases in Jerusalem on large chartered buses that drive almost directly to the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The tours rush the tourists in and out, and then take them to an enclosed restaurant and souvenir shop complex where the tourists eat and shop in a controlled environment. These tours are also notoriously non-political, that is, the guides are obliged not to speak of contemporary Palestinian life or politics, and instead focus on the ancient and biblical. Next to the pilgrimage enclave tours, the IPCRI Ramallah trip was alternative, and it certainly did not skirt around politics. In many ways, the day trip was designed around cultural and political flashpoints of Palestinian national recognition.

The cherry on the top of this IPCRI tour was a visit to Rawabi, the archetypical project of the Fayyadist economy and the vision for what life could be like in the future Palestinian state. Rawabi is an engineered gated community for the Palestinian bourgeoisie. It has been embroiled in controversy from all ends, criticized by Palestinians (and Uri Davis) for, amongst other things, accepting Israeli construction bids and originally accepting a donation of trees from the JNF. Israelis have criticized Israeli participants in the gated community for selling “the soul of Zionism and national solidarity for a handful of dollars." When normalization groups such as IPCRI or One Voice speak of a middle ground, free of extremism, it is places like Rawabi, a shining example of “economic peace,” that they have in mind. Rawabi has become a regular feature on a number of trips, including one organized by a major American Zionist organization, the American Jewish Committee. The trip was designed for US Mayors, and at their stop in Rawabi, one described it as marking “a significant change in the growth and development of a future Palestinian state living in peace (hopefully) with Israel.”

By now it should be clear that the outrage expressed by PA officials about the settlers at Solomon’s Pools was not echoed for this trip. On the contrary, Palestinian security forces acted as special escorts. There is money for such service, since as Amira Hass writes, the PA’s recently approved 2013 budget dedicates twenty-eight percent of the total to security. Needless to say, this budget does not even vaguely reflect the needs or priorities of most Palestinians, or even most Palestinian legislators. It was pushed through without time for any objections, as it has been every year since 2007. While Palestinians in the West Bank increasingly suffer from the devastated occupied economy, the most visible feature of the PA is its security forces. They can be seen repressing Palestinian demonstrations, imprisoning political dissidents, and in this case, escorting Israeli tourists around Ramallah.

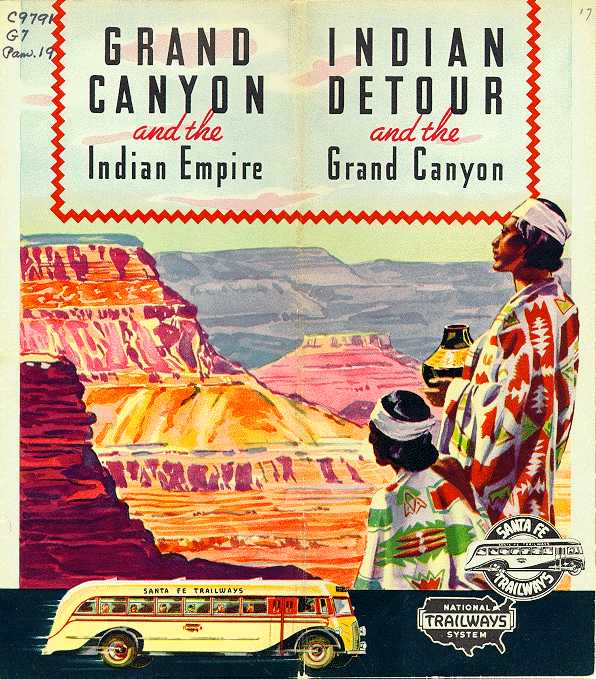

[Taken from a 1940`s advertisement for “Indian Detours,” special trips promoted on the Santa Fe Trailways in New Mexico designed for white settlers to view the “exotic peoples” of the Southwest. These tourists were called “detourists” and their trips considered a form of “off the beaten path” tourism." Grand Canyon and the Indian Empire; Indian Detour and the Grand Canyon [Wichita, Kansas: Santa Fe Trailways] Circa 1940s University of Arizona Library, Special Collections, “Southwest Wonderland”]

How should we understand the politics of this Israeli tour to Ramallah? One point made clear is that no matter what the PA or anyone else does or does not want, with just a bit of planning, Israelis can roll into whatever territory they want, whenever they want. This is as true today as it ever was. Israelis traveled in the West Bank ever since it was occupied in 1967, and not just as settlers. They went to go to tourist sites, do shopping, and fix their cars. The West Bank is still full of shops with signs in Hebrew, leftover from those days when Israeli civilians were around in much larger numbers. But with the second intifada, that flow of Israeli visitors to Palestinian cities in the West Bank was completely halted with the exception of some activists. Most others were scared to enter, and for good reason.

The recent return of Israeli civilians to West Bank cities does not mean that some mythical peace has arrived, or that Israelis by and large have become more open-minded, but rather that they feel secure enough in their safe domination again, at least in some parts of the West Bank, namely, Ramallah, Bethlehem, and Jericho, the area where the PA’s tourism development plans have been focused. For now they mostly stay on the bus, warming up to the experience, grateful to have the chance to satisfy their curiosity for seeing how the natives live. [3] This has been a feature of most settler-colonial societies, and while there may be areas that the settler population does not go, the visibility of settlers in multiple spaces shows an increased sense of security, at the cost of the basic freedoms of the native population. It does not indicate, as IPCRI would have us believe, a breakdown of social barriers between Israelis and Palestinians, or a substantial shift to the left amongst the Israeli public. This suggestion would be impossible to reconcile with all of the evidence to the contrary: growing popularity of openly racist and xenophobic Israeli political figures, an increase in violent attacks on individual Palestinians within Israel, as well as ongoing political and social repression of Palestinian politicians and activists inside Israel.

What seems more evident by the example of this trip is that spaces of Palestinian-ness and symbols of Palestinian identity feel increasingly non-threatening to Israelis, insofar as they are in museum form, as in the Darwish museum, or in the live mise en scene of the “Palestinian street” viewed from the bus. Similarly, a Palestinian state may seem less threatening when it is in isolated fragments, with a government who answers directly to Israel, and accompanied by the abandonment of Palestinian refugees. The Palestinian state promoted by the PA in diplomacy and in tourism and its Israeli allies (like Baskin) is one that has retained symbols from the Palestinian national struggle, detached them from their histories, and packaged them to gain support for a political path, which disenfranchises the already disenfranchised. Tourism is a part of imagining different kinds of political and material spaces. Israelis are getting used to the idea that Palestinians can have a state in Ramallah and that it will look like what they saw and along the way they can pretend that places like Nabi Saleh do not exist (all for $50 a day with IPCRI).

That these forms of tourism and types of spaces sit side by side, and often overlap, is reflective of the spatial and political fragmentation of the West Bank. The politics of tourism and travel is an important layer on these maps. Though they follow different itineraries, and are traveled by very different people with very different intentions, all of the forms of tourism that I discussed are travels within the same spatial regime. Within this regime, a listing of the different types of travel must also include (and foreground) the fact of highly restricted travel for most of the Palestinian inhabitants, and complete exclusion of most of the Palestinians in the world.

In this context, those involved or interested in solidarity tourism in Palestine must always be vigilant to see our travel in direct relation to the prohibited movement of most Palestinians. We must make clear and ethical distinctions between the “alternative” tourism that IPCRI (and many international and Palestinian groups as well) promote, and the practices of solidarity or resistance. If tourism can be a tool the powerful use to reinforce the spatial, political, and economic status quo, we must explore how tourism could support those who are building a resistance economy, based on exposing and rejecting the status quo and working from principles of justice and self-determination.

[1] The farce extends to differential treatment between different Israeli passport holders. While settlers and other Israeli Jewish citizens are given security escorts along with their permits when they cross into Area A, Palestinian citizens of Israel, who frequently travel to the West Bank to see family, shop, and visit for holidays, are often harassed at checkpoints, as described here and here. This rule also has bearing when Palestinians with Israeli citizenship choose to live in the West Bank. In this article when I use the term Israeli, I am referring only to Israeli Jews, unless indicated otherwise.

[2] Baskin’s most notable skill seems to be making himself extremely available for media appearances, most recently in Israel’s 2012 assault on Gaza when he was on every second independent news channel bemoaning how the Israeli attack had sabotaged negotiations that he was apparently singlehandedly brokering.

[3] In her book “Itineraries in Conflict,” Rebecca Stein analyzes a similar phenomenon of Israelis visiting Palestinian towns inside the State of Israel.